This year, (2026) the United States will mark two hundred and fifty years since its founding—a number that invites both celebration and unease, a round anniversary heavy with unfinished arguments, like those found in the reparations discussions this past December. As the nation rehearses its familiar story of revolution, expansion, rupture, and repair, the Baltimore Legacy column proposes a different vantage point: not the balcony view of history, but the street-level perspective of a city where national forces have long collided, coexisted, and been quietly reimagined.

Baltimore has always occupied a peculiar position in the American imagination—Southern and Northern, industrial and maritime, proud and wounded. It was here that the country’s largest free Black population once lived, worked, worshipped, and organized, creating a civic culture both fragile and formidable.

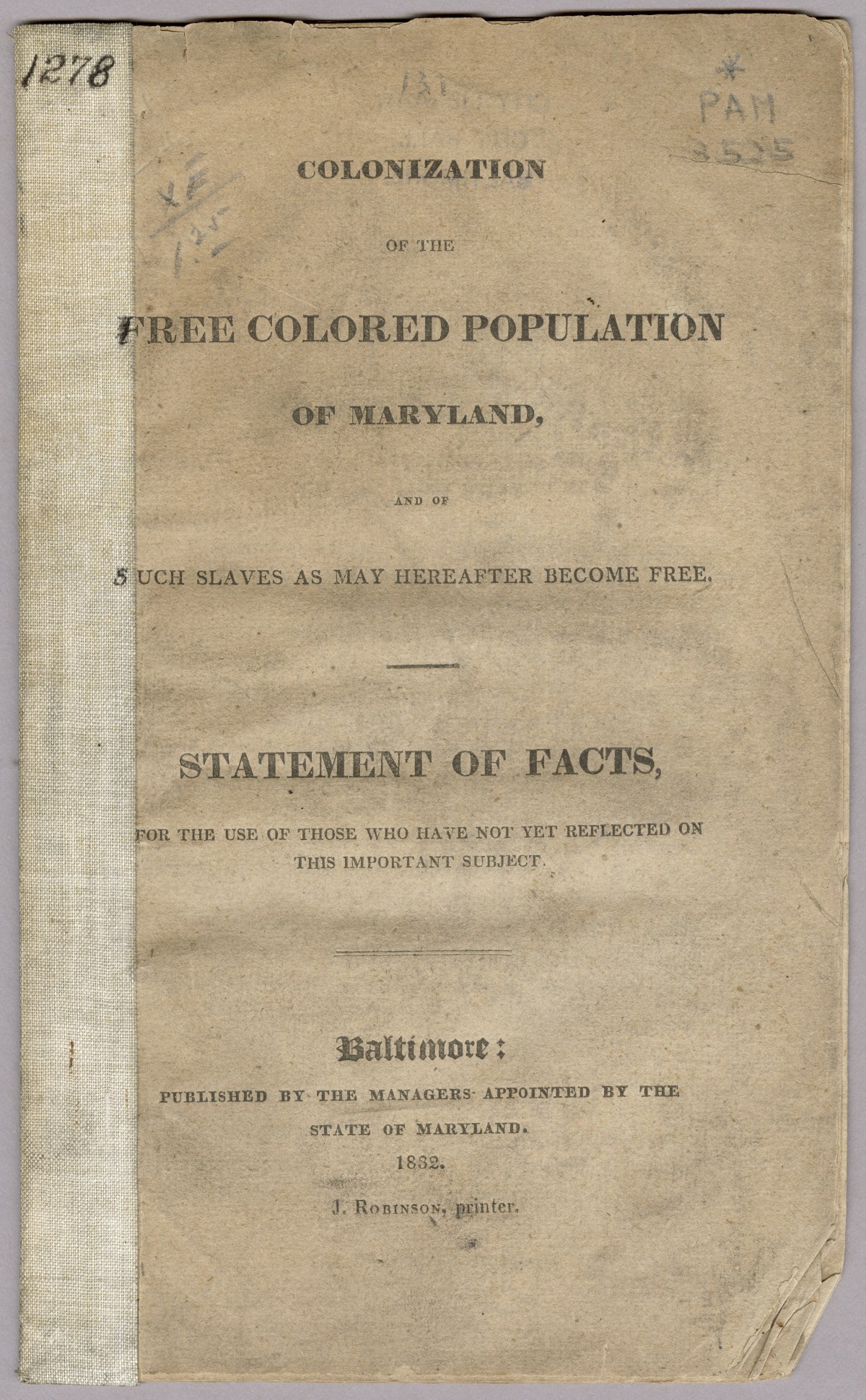

In the late nineteenth century, Maryland occupied an uneasy middle ground in the American imagination: a slave state by law, yet increasingly ambivalent in practice. Nowhere was this tension more apparent than in Baltimore, a city that quietly defied the prevailing logic of the South. While slavery continued to expand elsewhere below the Mason-Dixon Line, Baltimore was becoming something of an anomaly. By the early decades of the century, nearly ninety per cent of the city’s Black residents were free—a demographic fact that made Baltimore home to the largest free Black population in the nation. Some twenty-five thousand free Black people lived here, comprising roughly fifteen per cent of the city’s total population.

In 1810, Baltimore counted nearly five thousand enslaved people; by 1850, that figure had fallen to around three thousand. On the eve of the Civil War, only about one in ten African Americans in the city remained enslaved. As Henry Louis Gates, Jr., has observed, this gradual decline stood in sharp contrast to the entrenchment of slavery elsewhere in the South. Baltimore emerged as a magnet for free Black communities—dense, interconnected, and unusually visible for a Southern city.

Yet freedom, in Baltimore as in Maryland more broadly, was carefully circumscribed. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the state’s overwhelming white majority ensured that economic and political power remained out of reach. Free Black Baltimoreans built institutions, families, and neighborhoods, but were largely barred from the ranks of small business owners and civic leaders. Baltimore’s distinction, then, was not one of equality, but of contradiction: a city where freedom was widespread, fragile, and always negotiated within the shadow of slavery.

Maryland—and Baltimore in particular—stands as a living paradox in the American story. A slaveholding state that sustained the nation’s largest free Black city, it challenges the tidy binaries through which the past is often explained. Yet scholarship on this distinctive social reality remains surprisingly thin. Baltimore, with its surviving families, preserved records, and living memory, is uniquely positioned to illuminate this neglected chapter.

Dr. s. Rasheem

Dr. s. Rasheem is an Independent Scholar and Social Scientist whose scholarship encourages a critical examination of society and culture through the lens of race, gender, and class. Her educational background is interdisciplinary, and includes a Bachelors degree in Social Science, a minor in Sociology, a Masters’ in Nonprofit Management and a Doctorate of Philosophy in Social Work. She has been a Principal Investigator on at least five different qualitative research initiatives and has spoken on the topic of equity at over 30 academic and professional conferences.

The Baltimore Legacy Column is dedicated to uncovering and preserving the cultural memory of Baltimore through connecting the stories, reflections, and experiences of residents who witnessed and shaped the city’s evolution to the city's historical records. Ultimately, the Baltimore Legacy Column serves as a foundation to inform, inspire, and guide future generations of leaders in Baltimore City.